The AWO Federal Association explains: What is the anniversary about?

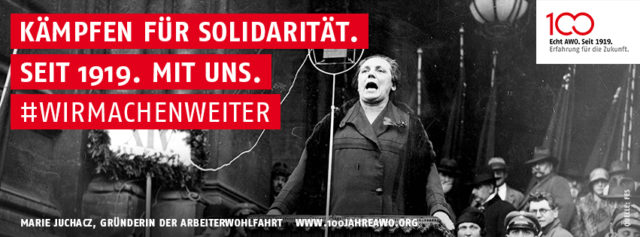

On 13 December 1919, the women’s rights activist and social politician, Marie Juchacz, successfully put forward the proposal to found a social democratic welfare organisation in the SPD party committee: The Main Committee for Workers’ Welfare was established. The text below gives an overview of the AWO’s almost 100-year history.

The founding of the AWO

After World War I, the German Reich was economically ruined and politically unstable. Millions of people were in need and starving. The war-disabled, the victims of the war, widows and orphans were largely without social assistance. Unprecedented mass impoverishment in Germany virtually challenged the self-help and practical solidarity of many volunteers. The idea of forming a social democratic welfare organisation out of the various organisations of the workers’ movement was obvious. But it was not only the current need of the people that led to the idea of a “workers’ welfare”. The political goal was to replace the stigmatising care for the poor of the old imperial regime and to carry the idea of self-help and solidarity into modern welfare work. Workers should no longer be merely the object of poor relief.

Friedrich Ebert, the first President of the German Reich, gave the young welfare association the motto: “Workers’ welfare is the self-help of the working class”. A social democratic welfare association was built up alongside the existing “bourgeois charity”. The democratisation of society and administrative structures was also one of the AWO’s goals. In order to achieve this goal also through a democratic understanding of the profession within the welfare workers and welfare nurses, the Main Committee for Workers’ Welfare founded its first welfare school in 1928. Since its foundation, the AWO has been a political interest group whose members advocate for social justice and social progress. However, the AWO was never a community exclusively serving the working class.

In the times of need in the 1920s, a multitude of services and institutions of the AWO came into being: sewing rooms, lunch tables, workshops, counselling centres. Many social democratic women and men were trained for a social profession. The aim of the AWO was to alleviate and prevent social hardship, to improve welfare services and to apply modern socio-educational methods. The discriminatory public “care of the poor” was to be gradually overcome by modern welfare legislation. Milestones on this path were the Reich Youth Welfare Act of 1922 and the Welfare Obligation Ordinance of 1924. The AWO demanded social legal rights. Its members had to cope with the devastating emergencies themselves just like those affected. The priority was therefore to counter the mass impoverishment with practical self-help. From 1925 onwards, the AWO organised its own lottery and sold workers’ welfare stamps to finance the social services that had been and were being created.

In 1926, the AWO was recognised as the Reichsspitzenverband der freien Wohlfahrtspflege. In 1931, 135,000 AWO volunteers were active in child recreation and protection, care for the elderly and youth welfare, emergency kitchens and workshops for the disabled and unemployed, and self-help sewing rooms.

The AWO became a helper organisation for all socially needy people, regardless of their origin and denomination.

Crushing of the AWO by the National Socialists

With the mobilisation and eventual seizure of power by the National Socialists in 1933, all the aims of the AWO – its work – were crushed. In the vote on the “Enabling Act” on 23 March 1933 in the “provisional” Reichstag, the 94 Social Democratic MPs present voted unanimously against it. 26 SPD MPs did not take part in the vote: they had been arrested or had already fled Germany. Otto Wels, as parliamentary party leader, gave a courageous speech against the destruction of democracy by the adoption of the law. Since the KPD was already banned, its 81 deputies were absent from the vote. This brought the constitution-amending majority of 444 votes through the approval of the bourgeois parties, above all the Centre. The parliamentary system and the judiciary were undermined. The office of the Main Committee for Workers’ Welfare at Belle Alliance Square in Berlin was occupied on 12 May 1933. Lotte Lemke, Executive Director of the AWO, was banned from the building. The AWO’s assets and property were confiscated.

With the law on the “confiscation of anti-people and anti-state assets” on 14 July 1933, the National Socialists “legitimised” their actions. The Main Committee for Workers’ Welfare was broken up. The withdrawal of its status as the Reichspitzenverband der Freien Wohlfahrtspflege finally took place on 25 July 1933.

Hitler’s attempts to transform the AWO into a National Socialist People’s Welfare Organisation failed, however. Leading men and women of the AWO were persecuted. As long as funds permitted, help for those in need and persecuted by the Nazi regime continued illegally. Marie Juchacz and many others had to leave Germany to escape persecution. In New York, Marie Juchacz founded the Workers’ Welfare Association USA to provide help for the victims of National Socialism. She was instrumental in getting Workers’ Welfare involved in the CARE package drive after the war ended. At times, the post office counted more than one million parcels per month sent to Germany on Marie Juchacz’s initiative.

New beginning and reconstruction

With the end of the war in 1945, the collapse and division of the German Reich, reconstruction began in Germany occupied by the Allies; immediately after the end of the war was also the new start and reconstruction of the AWO. It was re-established in Hanover in 1946 as a politically and denominationally independent and autonomous organisation.

The AWO was no longer permitted in the Soviet occupation zone. In Berlin, due to the four-power status, it had an official licence for the eastern part of the city until 1961.

Persecution, destruction, war and devastation had not been able to destroy the ideas of the AWO. Local associations of the Workers’ Welfare Association courageously resumed their work in the western occupation zones. AWO helpers cared for evacuees and refugees, those returning home, the old and the lonely, and young people who had lost their homes and parents.

Children’s and youth recreation programmes were offered again, sewing workshops were opened in accordance with the old tradition, as well as home economics and maternity education facilities. In 1949, there were already 50,000 volunteers and 300,000 friends and members of the AWO in the three western occupation zones and Berlin.

Experience for the future

The social constitutional state, as the AWO aspired to at its beginnings and when becoming what it is now, has become reality to a large extent. However, the AWO does not let up in its demands for reforms and changes in social policy, in health policy, in family policy and in general care for people and their social security. It has always brought its demands to parliaments and governments. This has resulted in laws that guarantee legal rights to social assistance. One example among many is the social security of the risk of long-term care. The AWO has taken on new social tasks that have their origins in the changes in society. These include the care of the numerous “foreign workers”, who were dubbed “foreign workers” at the time, since the beginning of the 1960s, inpatient and outpatient care for the elderly, early childhood education in crèches, kindergartens and after-school care centres, pioneering work in the field of speech therapy, the development of modern housing concepts for the elderly, addiction counselling and socio-psychological care. The principle of the AWO’s social work continues to be helping people to help themselves. In all areas, the AWO attaches importance to solving social tasks of the present with a view towards the future – with experience for the future!

ABOUT US

ABOUT US